A staff member of the Christian charity Samaritan's Purse disinfects the

premises outside the ELWA hospital in the Liberian capital Monrovia on

July 24, 2014 as cases of Ebola mount (AFP Photo/Zoom Dosso)

It is a sweltering morning in the over-stretched Ebola clinic in the Liberian capital Monrovia, and Kendell Kauffeldt scowls in frustration as a jeep pulls up with a new patient.

"It's dangerous to bring cases in private vehicles like this," he chides as he watches the Toyota disgorge its five passengers at the main gate

See more news and photos after the cuts..........

People walk past the empty Red Light market in Monrovia after it was closed along with shops and offices as part of a disinfection campaign against Ebola, on August 1, 2014 (AFP Photo/Zoom Dosso)

"It's dangerous to bring cases in private vehicles like this," he chides as he watches the Toyota disgorge its five passengers at the main gate.

"The ministry of health has established protocols. There are hotline numbers that people have to call. And when you call there are ambulances, with trained people on board who are protected, to take the patient to hospital."

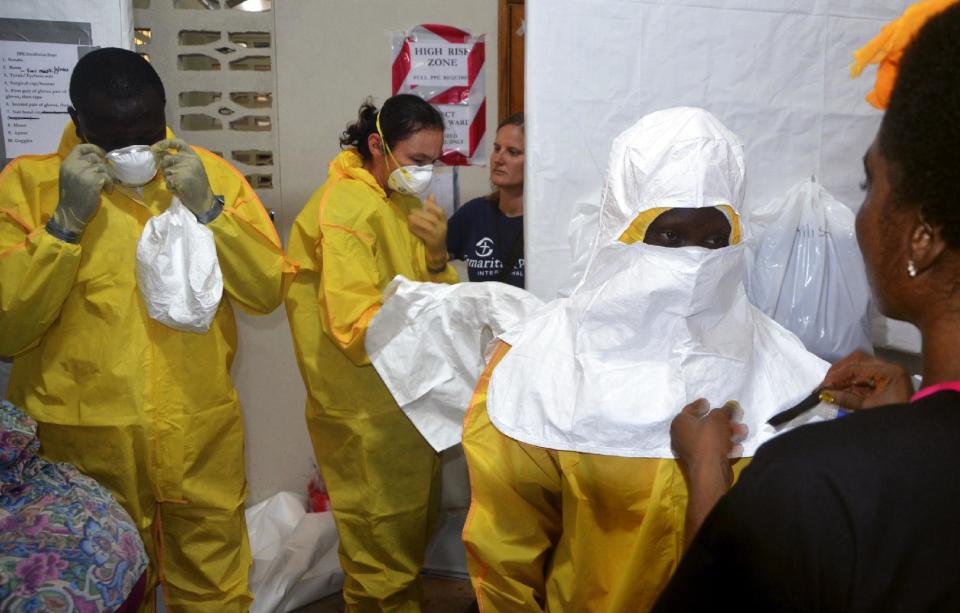

Staff of Christian charity Samaritan's Purse put on protective gear in the ELWA hospital in Liberia's capital Monrovia on July 24, 2014 (AFP Photo/Zoom Dosso)

Kauffeldt, the director in Liberia of Christian aid group Samaritan's Purse, is at the forefront of the country's battle with the worst outbreak of Ebola that the world has ever seen.

More than 300 Liberians have been infected by the tropical virus, which has been raging in west Africa's forests since the start of the year. More than half of those who have caught the disease have died.

A 10-year-old boy walks with a doctor from Christian charity Samaritan's Purse, after being taken out of quarantine and receiving treatment following his mother's death from Ebola, at the ELWA hospital in Monrovia, on July 24, 2014 (AFP Photo/Zoom Dosso)

But Kauffeldt and other aid workers warn that it is ignorance over Ebola, rather than the virus itself, that is pushing up the death toll.

Ebola is a terrifying spectre for the people of Liberia's remote forests, who have seen relatives die in agonising pain.

A staff member of the Christian charity Samaritan's Purse treats the area at the entrance of the ELWA hospital in the Liberian capital Monrovia on July 24, 2014 (AFP Photo/Zoom Dosso)

The virus can fell its victims within days, delivering severe muscle pain, headaches, vomiting, diarrhoea and, in most cases, unstoppable bleeding as the patient's organs break down and seep out of their bodies.

- Damaging myths -

Protective gear including boots, gloves, masks and suits, are left to dry after being used to treat Ebola patients in the Liberian capital Monrovia, on July 24, 2014 (AFP Photo/Zoom Dosso)

Yet the pathogen itself is not particularly robust, and can be seen off with soap and hot water.

Epidemiologists point out that Ebola is relatively difficult to catch and isn't even airborne.

In this 2014 photo provided by the Samaritan's Purse aid organization, Dr. Kent Brantly, left, treats an Ebola patient at the Samaritan's Purse Ebola Case Management Center in Monrovia, Liberia. On Saturday, July 26, 2014, the North Carolina-based aid organization said Brantly tested positive for the disease and was being treated at a hospital in Monrovia. (AP Photo/Samaritan's Purse)

The virus requires contact with the bodily fluids of a victim -- their blood, urine, faeces, vomit, saliva or sweat -- to leap into a new host.

For those unlucky enough to catch Ebola, the disease it brings about is also treatable, say experts.

Dr. Kent Brantly (R) speaks with colleagues at the case management center on the campus of ELWA Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia in this undated handout photograph courtesy of Samaritan's Purse. REUTERS/Samaritan's Purse/Handout via Reuters

Patients who are kept hydrated, given paracetamol to keep their temperature in check and treated with antibiotics for secondary infections have a fighting chance of recovery.

Medical staff working with Medecins sans Frontieres (MSF) prepare to bring food to patients kept in an isolation area at the MSF Ebola treatment centre in Kailahun. Sierra Leone now has the highest number of Ebola cases, at 454, surpassing neighbouring Guinea where the outbreak originated in February. Picture taken July 20, 2014. REUTERS/Tommy Trenchard

But in a country where remote communities are deeply superstitious of western medicine and often rely on the wisdom of witch doctors, a variety of damaging myths have built up around Ebola.

Dr. Kent Brantly wears protective gear at the case management center on the campus of ELWA Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia

Among the most worrisome is the widespread belief that Ebola is a western conspiracy or doesn't exist at all. Another is that entering an Ebola treatment centre is accepting a death sentence.

In the new clinic set up by the charity Samaritan's Purse in Monrovia's ELWA hospital, up to 10 new cases are registered every day.

"With communication and education not robust as they should be, we see this happening where Ebola cases are brought in taxis or private cars," Kauffeldt tells AFP.

"This is very worrisome because everybody in that car has had contact with the patient. We need to watch them for 21 days to know whether they have been infected."

- Admitting Ebola is real -

It's not just taxi drivers who have to worry. Ebola patients, ignorant of the risks, are putting their own family members in grave danger.

Ten-year-old William Benedict, one of the clinic's success stories, has made a full recovery against the odds after catching the virus from his dying mother.

"I was near mama when she was sick. When she died, I got sick," William says as he prepares to leave the centre and return to his village.

James Kollie, the clinic's ambulance driver, explains that the boy's mother summoned her son to lie beside her as she was dying in bed, coughing, vomiting and generally presenting a grave risk to anyone nearby.

"I drove the vehicle that carried the team to pick him up. That day everybody was running from him. I shed tears for him," Kollie tells AFP.

On Friday the leaders of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea agreed a $100 million emergency action plan to beef the response to Ebola.

Much of the cash will go on deploying medical workers. But the plan also includes provision to improve education throughout the Ebola zone straddling the three countries.

Lawmaker Peter Coleman, the head of Liberia's Senate Committee on Health, says the poverty endemic across the country has been a major obstacle to spreading reliable information.

"The majority of Liberians don’t have access to radio. In our villages only few people can get radio messages," he told AFP.

Two Americans working in Africa have tested positive for the deadly Ebola virus. Both are part of a team combating an alarming outbreak in West Africa that has killed at least 672 people since February. Mark Albert reports.

"There should be a campaign from village to village, from community to community, from town to town, even from door to door."

Samaritan's Purse, which runs all three of Liberia's treatment centres with help from other aid agencies and the government, believes education is as important as medicine in saving lives.

"We have to admit, Ebola is real. People are dying of Ebola and they don’t have to die of Ebola," Kauffeldt said.

"If they come and seek treatment early they will survive."

No comments:

Post a Comment